A while ago I wrote about the Boston Marathon and Mount Everest being common (im)possible dreams. I noted in that post that my neurologist had done the Boston Marathon (I think), and that my friend and I ‘mostly’ made it up the Nepalese mountain to reach Annapurna base camp, when we were both 19 years old, as part of our pseudo-Mt-Everest-dream. The reason for the strange word choice of ‘mostly’ is that he made it up the mountain – I didn’t. I thought it was worth writing about, because reaching that pinnacle-point was our (im)possible dream, the whole reason we were there, and my ‘failure’ to succeed turned out to be the most difficult – and wonderful – part of our trip.

I used to have tonsilitis on a regular basis as a child, often a couple of times a year, every year, for several years in a row. Doctors assumed that it was due to these recurring bouts of tonsilitis that I never grew as tall as my 6-foot-plus parents, or my sisters who, although they were younger, were far taller than me. I’m telling you this seemingly sidetracked information, because, when I was on the mountain in Nepal and my throat started to hurt, I recognized the symptoms and knew that I was getting sick.

Having trekked for several days, we could calculate from our maps that we were about 2-3 days from our ‘summit’; the highest point you can get to before you switch from ‘hiking’ to ‘mountaineering’. (I might not be right, or things may have since changed, but that’s my memory of the Annapurna-situation from the early 1990s.) By that stage of the trek, we were already getting to a higher altitude and breathing was getting harder (obviously nothing compared to Mt Everest difficult, but the difference WAS noticeable). Breathing at altitude makes you feel as if you have to breathe deeper and more often to get enough of the oxygen your moving body requires. Having tonsilitis on the other hand, makes breathing raspy and painful, so you do your best to avoid it.

As stoic as I was trying to be, I was slowing us down, and my friend and I both realized I wasn’t going to make it up the mountain while I was sick. We were only in Nepal for so many days and had a flight booked back to Australia, so there was no time to hang about and heal. Whilst it seemed ‘obvious’ that he should go on while I stayed behind, we had made a pact at the beginning of the trip that we would never leave each other’s side. I really hated the idea of not achieving my dream, but I hated it even more that I would be the reason that his dream was ruined. I wasn’t too scared to stay put for 4-6 days (2-3 days up / 2-3 days down), but the idea of him travelling alone into the wilderness wasn’t ideal. We’d been hearing gossip from other travelers that you might have to camp out in a tent on the last night, and that would make it harder if he had to carry all the equipment alone.

The way I remember it, as we were deliberating, three New Zealand tourists met us on the path. They were going up to Annapurna base camp and welcomed my friend to travel with them the next day. It was agreed; he would go up the mountain, and I would stay behind.

We found a house to seek accommodation in. The way it worked, back then at least, is that there were no hotels or formal lodges for the tourists who passed through. Instead, regular homes let you stay in their spare bedroom for a night. I guess it was a traditional Bed & Breakfast arrangement, or a precursor to AirBnB. As two best buddies, and nothing more, we stayed the night, chastely side by side in our separate sleeping bags, BUT, because we had worn wedding rings to make it easier to share rooms when we travelled, our hosts assumed we really were married. When he left to go up the mountain in the morning, and I stood glumly on the doorstep waving goodbye, our hosts thought he had abandoned me.

What happened next was astounding: I was adopted.

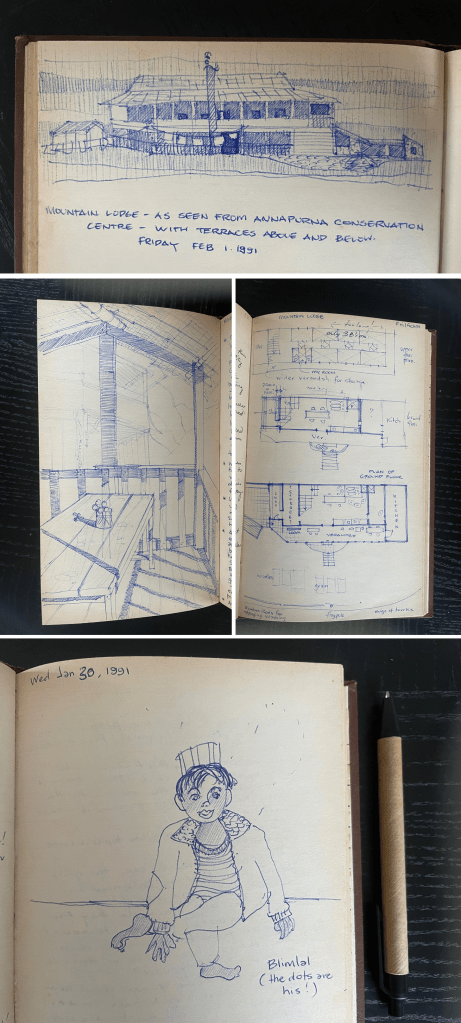

Whilst I couldn’t be sure of who was related to who, or how, over the next few days one woman in the house taught me how to make the family’s noodles, whilst another showed me how to work the loom. One of the kids took me to school where I spent a day playing with the kids, and the afternoon with one of the gentlemen helping mend a stone wall. I even became a minor local celebrity when I drew some (iffy) sketches of some of the townspeople for them to keep (some of my diary sketches from the trip are reproduced below (and yes, I really do hold onto diaries for 30+ years!)).

Each day that the family woke, and found me still there, the kinder they were, and the harder I tried, and failed, to explain that I was not staying forever.

One of my favorite routines of the day involved the elders. There were three grandparents, (or great-grandparents?), whose ‘job’ was to lie on a blanket in the sun, in the garden. As the sun moved, and the shade fell on the blanket, it was everyone else’s job to carry them on their blankets to a new location. It seemed an intensely respectful way to wordlessly say; “thank you for all that you have done over the years, now it’s your turn to rest, let me help you”. One day, to my astonishment, the three elders stood up and started waving, clapping, singing and dancing. I had barely seen them move since I’d arrived, and nothing this animated. The rest of the family came out of the house and appeared equally bemused. We all looked towards what they were so excited about… it was my friend coming down the mountain.

Everyone rushed to get him and forced us into an uncomfortable embrace. My friend was whispering questions, and I was just saying “look like you’re happy to see me – act like you’ve decided to take me home.” We all enjoyed a celebratory dinner that night, and my friend told me of his great joy at making it to the place we had dreamed of, and how he was lucky to have gone with new friends because he would have been underprepared if he’d gone alone. I told him of all that I had been up to, and in the morning, it felt like the whole town came out to wave us good bye and good luck.

Was I sad that I didn’t make it up the mountain? You bet. BUT – and it’s a big, capital-letter but – what I got in return for ‘failing’ and being sick, was an experience unlike anything I could have imagined. There were several amazing moments on our trip through India and Nepal, including, standing in front of the Taj Mahal and ‘reading’ the love poem of the building, with its unification of masculine and feminine forms (turrets and domes), as well as the incredibly moving night we spent at the ‘burning ghats’ on the Ganga (Ganges) River in Varanasi, where families come to cremate their loved ones, and send their ashes down the river and into the next life. Being a Nepalese house-wife or adopted daughter, however, was perhaps the most special because it was the most personal and unexpected.

It was a long story (sorry), but it has a short moral; sometimes being sick is a gift. Or perhaps; sometimes you win big when you fail – so, don’t be afraid to fail.

Take care and keep dreaming your (im)possible dreams; who knows where they might take you, Linda x

PS – Here is a blog post that reviews trekking in Nepal and includes several maps and pictures of Ghandruk (the village where I stayed), including this fabulous one:

PPS – if you were tempted to follow our footsteps, I also found this accommodation for you in Ghandruk. The company says it was established in 1991 (the same year we were there) and the accommodation “offers altitude, superb views of mountains and terraced fields, and plenty of roaming wildlife. From here, some continue on to Annapurna Base Camp” [note – SOME people continue on!!!]. It also mentions that the bedrooms have ensuites… which is certainly NOT how I remember it. Times have changed I guess – hopefully for the better for Blimlal (who I drew) and the rest of the Nepalese family members I stayed with. xx

Leave a reply to Wynne Leon Cancel reply